Skip Navigation

Articles

March 6, 2026 · Adrianne Evans

Foodie Finds: Our favorite kitchen tools

After quizzing family & friends Adrianne reveals people's favorite kitchen tools and why. You might find some new items to add to your collection or bring out of the back of the drawer.

March 6, 2026 · Adrianne Evans

Foodie Finds: Our favorite kitchen tools

After quizzing family & friends Adrianne reveals people's favorite kitchen tools and why. You might find some new items to add to your collection or bring out of the back of the drawer.

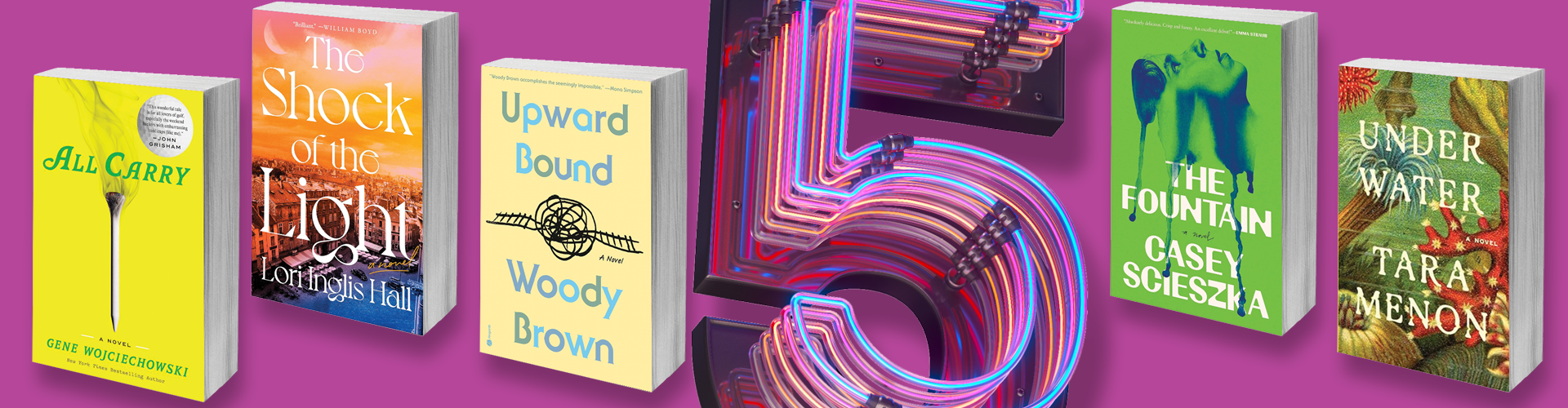

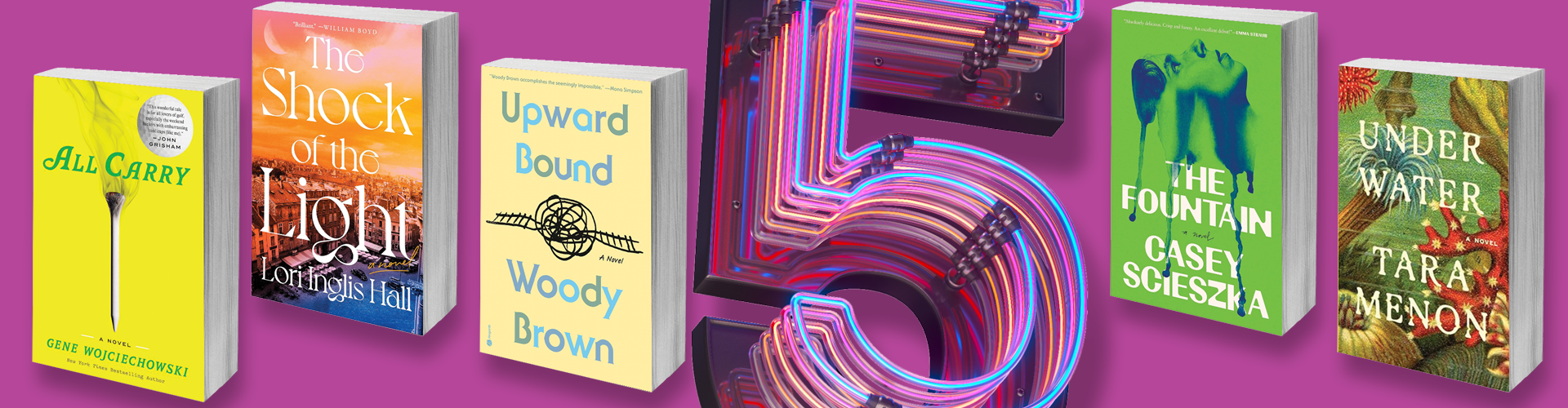

March 5, 2026 · Chris Blocker

Fiction Five: Dazzling Debuts

With spring just around the corner let's celebrate new beginnings with new authors. We're highlighting five wonderfully unique fiction debuts.

March 5, 2026 · Chris Blocker

Fiction Five: Dazzling Debuts

With spring just around the corner let's celebrate new beginnings with new authors. We're highlighting five wonderfully unique fiction debuts.

February 27, 2026 · Abigail Siemers

What YA' Reading: Graphic Novels

Graphic Novels tell a story in a visual and written format with illustrations that bring the story to life. The novels are as complex and varied as the authors themselves.

February 27, 2026 · Abigail Siemers

What YA' Reading: Graphic Novels

Graphic Novels tell a story in a visual and written format with illustrations that bring the story to life. The novels are as complex and varied as the authors themselves.

February 27, 2026 · Lane Wiens, Shawnee County Horticulture Extension Agent

Master Gardeners help your garden grow

Learn about growing in small spaces, garden design, wildflower lawns and more help from Shawnee County K-State Extension.

February 27, 2026 · Lane Wiens, Shawnee County Horticulture Extension Agent

Master Gardeners help your garden grow

Learn about growing in small spaces, garden design, wildflower lawns and more help from Shawnee County K-State Extension.

February 27, 2026 · Kaitlyn Kriley

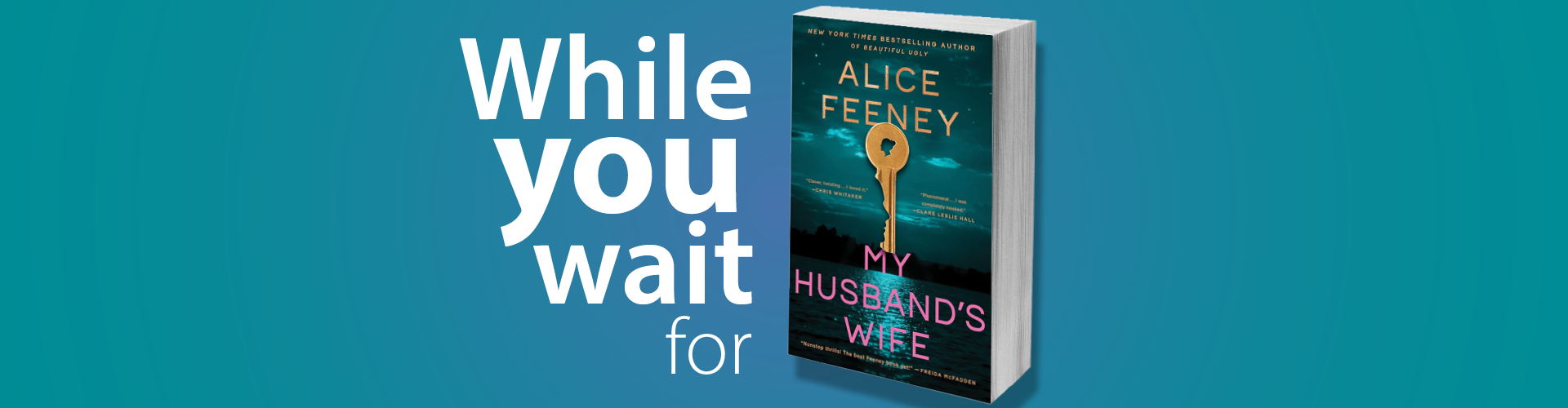

While you wait for My Husband's Wife

Unravel domestic thrillers filled with simmering secrets, shocking twists and no one to trust.

February 27, 2026 · Kaitlyn Kriley

While you wait for My Husband's Wife

Unravel domestic thrillers filled with simmering secrets, shocking twists and no one to trust.

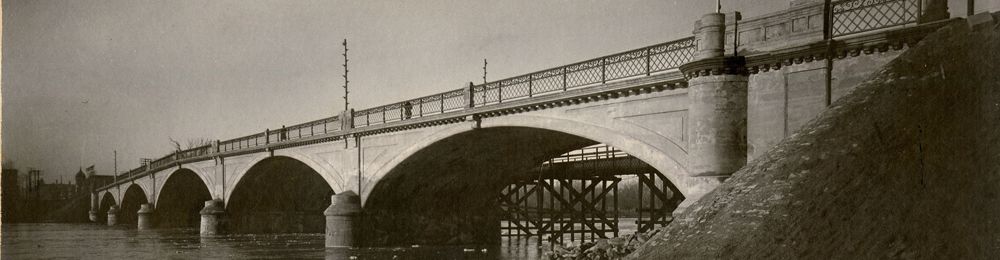

February 26, 2026 · Katie Keckeisen

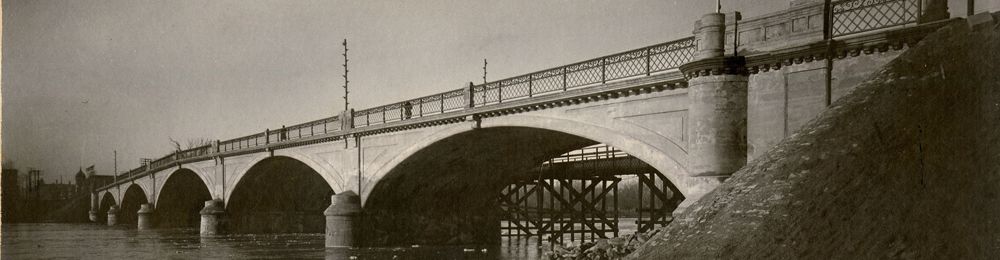

Local History: The rise and fall of Topeka's Melan Bridge

Between 1858 & 1895 several bridges spanned the river at today's Kansas Ave, but none of them could withstand the regular flooding. In 1898 a bridge was finally built that was thought would last as long as the city itself.

February 26, 2026 · Katie Keckeisen

Local History: The rise and fall of Topeka's Melan Bridge

Between 1858 & 1895 several bridges spanned the river at today's Kansas Ave, but none of them could withstand the regular flooding. In 1898 a bridge was finally built that was thought would last as long as the city itself.

February 26, 2026 · Brittany Keegan

Runway Remix: Fashion in Focus

Seven artists developed original pieces of wearable fiber art inspired by pieces from the library’s permanent art collection.

February 26, 2026 · Brittany Keegan

Runway Remix: Fashion in Focus

Seven artists developed original pieces of wearable fiber art inspired by pieces from the library’s permanent art collection.

February 25, 2026 · Debbie Updegraff

Great Read Alouds: Get to know interesting people

Read picture book biographies to learn about history and the fascinating people who made big changes to our world.

February 25, 2026 · Debbie Updegraff

Great Read Alouds: Get to know interesting people

Read picture book biographies to learn about history and the fascinating people who made big changes to our world.

February 24, 2026 · Nessa Johnson

The Reel World: Gardening with the experts

Dig into fascinating and informative DVDs about gardening to get ready for spring.

February 24, 2026 · Nessa Johnson

The Reel World: Gardening with the experts

Dig into fascinating and informative DVDs about gardening to get ready for spring.

February 23, 2026 · Liza Charay

Celebrating Black History Month with music

Check out three of Liza's favorite artists to celebrate Black History Month with! These Black American artists never fail to put a smile on her face and get her dancing.

February 23, 2026 · Liza Charay

Celebrating Black History Month with music

Check out three of Liza's favorite artists to celebrate Black History Month with! These Black American artists never fail to put a smile on her face and get her dancing.

February 18, 2026 · Angela Portzer

5 Ways to draw like a kid again

If the fear of making “bad” art is keeping you from drawing to your heart’s content, we've got ways to keep you making happy art.

February 18, 2026 · Angela Portzer

5 Ways to draw like a kid again

If the fear of making “bad” art is keeping you from drawing to your heart’s content, we've got ways to keep you making happy art.

February 13, 2026 · Jacee Gleason

Kid Tested, Librarian Recommended: Graphic novels kids devour

These graphic novels hook kids with humor and heart, support literacy skills, and keep kids coming back for more.

February 13, 2026 · Jacee Gleason

Kid Tested, Librarian Recommended: Graphic novels kids devour

These graphic novels hook kids with humor and heart, support literacy skills, and keep kids coming back for more.

February 9, 2026 · Julie Nelson

Lost in the Stacks: The Way Out

Got a ski trip coming up? Read this cautionary tale before you hit the powder.

February 9, 2026 · Julie Nelson

Lost in the Stacks: The Way Out

Got a ski trip coming up? Read this cautionary tale before you hit the powder.

February 5, 2026 · Chris Blocker

Fiction Five: Robust Romances

Uncover five new novels that’ll make your heart race and have you falling in love.

February 5, 2026 · Chris Blocker

Fiction Five: Robust Romances

Uncover five new novels that’ll make your heart race and have you falling in love.

February 2, 2026 · Ginger Park

Recent library trivia winners

See the teams who won September's Library Trivia – Evening Edition and Afternoon Edition.

February 2, 2026 · Ginger Park

Recent library trivia winners

See the teams who won September's Library Trivia – Evening Edition and Afternoon Edition.

January 27, 2026 · Kaitlyn Kriley

While you wait for Theo of Golden

Peruse compelling novels that explore the importance of community and connection.

January 27, 2026 · Kaitlyn Kriley

While you wait for Theo of Golden

Peruse compelling novels that explore the importance of community and connection.

January 27, 2026 · Brea Black

Artsy Crafty Library: More crafting, less scrolling

Many crafters find working with their hands is a good way to lower stress & improve well-being. Whether you're looking to learn new craft skills or to further your knowledge, the library has resources to help.

January 27, 2026 · Brea Black

Artsy Crafty Library: More crafting, less scrolling

Many crafters find working with their hands is a good way to lower stress & improve well-being. Whether you're looking to learn new craft skills or to further your knowledge, the library has resources to help.

January 26, 2026 · Stephen Ferrell

3 Classic rock albums move from lost to found

Thanks to some spiffy new re-releases you can discover long-lost classic rock treasures.

January 26, 2026 · Stephen Ferrell

3 Classic rock albums move from lost to found

Thanks to some spiffy new re-releases you can discover long-lost classic rock treasures.

January 23, 2026 · Luanne Webb

Great Read Alouds: Cozy winter reads

Check out our recommendations of picture books that can kick-start the love of reading.

January 23, 2026 · Luanne Webb

Great Read Alouds: Cozy winter reads

Check out our recommendations of picture books that can kick-start the love of reading.

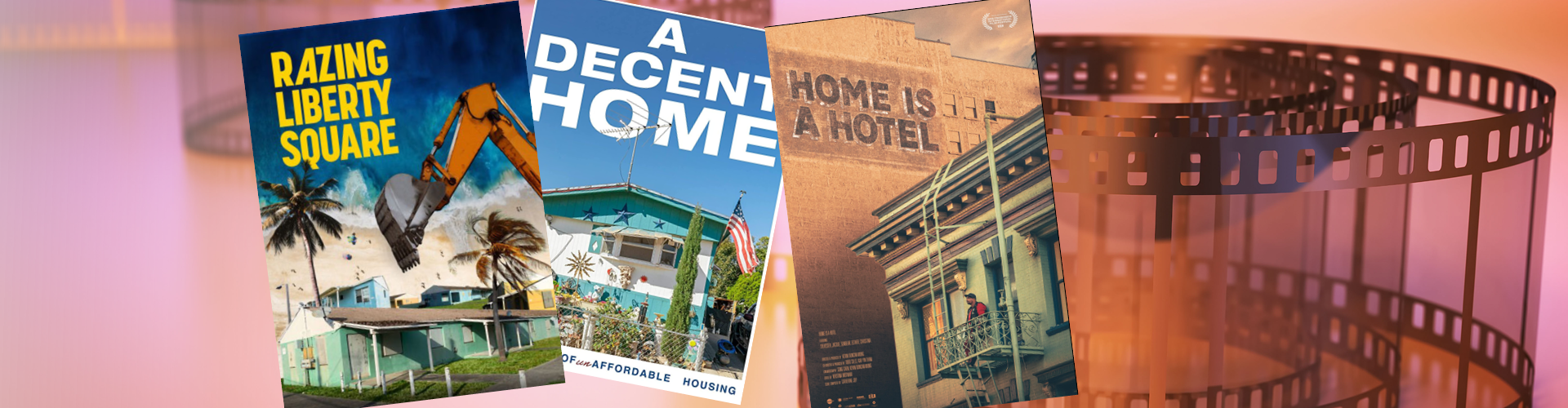

January 23, 2026 · Julie Nelson

The Reel World: No place to call home

Watch documentaries that take you across the country to visit communities struggling with affordable housing.

January 23, 2026 · Julie Nelson

The Reel World: No place to call home

Watch documentaries that take you across the country to visit communities struggling with affordable housing.

January 22, 2026 · Katie Keckeisen

Discover an easier way to access local history materials

The library is home to a robust collection of items relating to Topeka and Shawnee County history including archives, photographs, ephemera and three-dimensional objects.

January 22, 2026 · Katie Keckeisen

Discover an easier way to access local history materials

The library is home to a robust collection of items relating to Topeka and Shawnee County history including archives, photographs, ephemera and three-dimensional objects.

January 15, 2026 · Arion Beals

Kid Tested, Librarian Recommended: Kids classics

Classic stories are a little like a favorite blanket. They make you feel warm and cozy, and make you want to come back to them again and again.

January 15, 2026 · Arion Beals

Kid Tested, Librarian Recommended: Kids classics

Classic stories are a little like a favorite blanket. They make you feel warm and cozy, and make you want to come back to them again and again.

January 13, 2026 · Andrew Ross

What YA' Reading: Sci-Fi Romance

Read every Romantasy there is? Check out captivating Sci-Fi stories with plot-central romances next.

January 13, 2026 · Andrew Ross

What YA' Reading: Sci-Fi Romance

Read every Romantasy there is? Check out captivating Sci-Fi stories with plot-central romances next.

January 12, 2026 · Julie Nelson

Lost in the Stacks: Sisters in Death

Discover an intriguing link between the infamous Black Dahlia case and a gruesome murder in Kansas City.

January 12, 2026 · Julie Nelson

Lost in the Stacks: Sisters in Death

Discover an intriguing link between the infamous Black Dahlia case and a gruesome murder in Kansas City.

Back to Top

March 6, 2026 · Adrianne Evans

Foodie Finds: Our favorite kitchen tools

After quizzing family & friends Adrianne reveals people's favorite kitchen tools and why. You might find some new items to add to your collection or bring out of the back of the drawer.

March 6, 2026 · Adrianne Evans

Foodie Finds: Our favorite kitchen tools

After quizzing family & friends Adrianne reveals people's favorite kitchen tools and why. You might find some new items to add to your collection or bring out of the back of the drawer.

March 5, 2026 · Chris Blocker

Fiction Five: Dazzling Debuts

With spring just around the corner let's celebrate new beginnings with new authors. We're highlighting five wonderfully unique fiction debuts.

March 5, 2026 · Chris Blocker

Fiction Five: Dazzling Debuts

With spring just around the corner let's celebrate new beginnings with new authors. We're highlighting five wonderfully unique fiction debuts.

February 27, 2026 · Abigail Siemers

What YA' Reading: Graphic Novels

Graphic Novels tell a story in a visual and written format with illustrations that bring the story to life. The novels are as complex and varied as the authors themselves.

February 27, 2026 · Abigail Siemers

What YA' Reading: Graphic Novels

Graphic Novels tell a story in a visual and written format with illustrations that bring the story to life. The novels are as complex and varied as the authors themselves.

February 27, 2026 · Lane Wiens, Shawnee County Horticulture Extension Agent

Master Gardeners help your garden grow

Learn about growing in small spaces, garden design, wildflower lawns and more help from Shawnee County K-State Extension.

February 27, 2026 · Lane Wiens, Shawnee County Horticulture Extension Agent

Master Gardeners help your garden grow

Learn about growing in small spaces, garden design, wildflower lawns and more help from Shawnee County K-State Extension.

February 27, 2026 · Kaitlyn Kriley

While you wait for My Husband's Wife

Unravel domestic thrillers filled with simmering secrets, shocking twists and no one to trust.

February 27, 2026 · Kaitlyn Kriley

While you wait for My Husband's Wife

Unravel domestic thrillers filled with simmering secrets, shocking twists and no one to trust.

February 26, 2026 · Katie Keckeisen

Local History: The rise and fall of Topeka's Melan Bridge

Between 1858 & 1895 several bridges spanned the river at today's Kansas Ave, but none of them could withstand the regular flooding. In 1898 a bridge was finally built that was thought would last as long as the city itself.

February 26, 2026 · Katie Keckeisen

Local History: The rise and fall of Topeka's Melan Bridge

Between 1858 & 1895 several bridges spanned the river at today's Kansas Ave, but none of them could withstand the regular flooding. In 1898 a bridge was finally built that was thought would last as long as the city itself.

February 26, 2026 · Brittany Keegan

Runway Remix: Fashion in Focus

Seven artists developed original pieces of wearable fiber art inspired by pieces from the library’s permanent art collection.

February 26, 2026 · Brittany Keegan

Runway Remix: Fashion in Focus

Seven artists developed original pieces of wearable fiber art inspired by pieces from the library’s permanent art collection.

February 25, 2026 · Debbie Updegraff

Great Read Alouds: Get to know interesting people

Read picture book biographies to learn about history and the fascinating people who made big changes to our world.

February 25, 2026 · Debbie Updegraff

Great Read Alouds: Get to know interesting people

Read picture book biographies to learn about history and the fascinating people who made big changes to our world.

February 24, 2026 · Nessa Johnson

The Reel World: Gardening with the experts

Dig into fascinating and informative DVDs about gardening to get ready for spring.

February 24, 2026 · Nessa Johnson

The Reel World: Gardening with the experts

Dig into fascinating and informative DVDs about gardening to get ready for spring.

February 23, 2026 · Liza Charay

Celebrating Black History Month with music

Check out three of Liza's favorite artists to celebrate Black History Month with! These Black American artists never fail to put a smile on her face and get her dancing.

February 23, 2026 · Liza Charay

Celebrating Black History Month with music

Check out three of Liza's favorite artists to celebrate Black History Month with! These Black American artists never fail to put a smile on her face and get her dancing.

February 18, 2026 · Angela Portzer

5 Ways to draw like a kid again

If the fear of making “bad” art is keeping you from drawing to your heart’s content, we've got ways to keep you making happy art.

February 18, 2026 · Angela Portzer

5 Ways to draw like a kid again

If the fear of making “bad” art is keeping you from drawing to your heart’s content, we've got ways to keep you making happy art.

February 13, 2026 · Jacee Gleason

Kid Tested, Librarian Recommended: Graphic novels kids devour

These graphic novels hook kids with humor and heart, support literacy skills, and keep kids coming back for more.

February 13, 2026 · Jacee Gleason

Kid Tested, Librarian Recommended: Graphic novels kids devour

These graphic novels hook kids with humor and heart, support literacy skills, and keep kids coming back for more.

February 9, 2026 · Julie Nelson

Lost in the Stacks: The Way Out

Got a ski trip coming up? Read this cautionary tale before you hit the powder.

February 9, 2026 · Julie Nelson

Lost in the Stacks: The Way Out

Got a ski trip coming up? Read this cautionary tale before you hit the powder.

February 5, 2026 · Chris Blocker

Fiction Five: Robust Romances

Uncover five new novels that’ll make your heart race and have you falling in love.

February 5, 2026 · Chris Blocker

Fiction Five: Robust Romances

Uncover five new novels that’ll make your heart race and have you falling in love.

February 2, 2026 · Ginger Park

Recent library trivia winners

See the teams who won September's Library Trivia – Evening Edition and Afternoon Edition.

February 2, 2026 · Ginger Park

Recent library trivia winners

See the teams who won September's Library Trivia – Evening Edition and Afternoon Edition.

January 27, 2026 · Kaitlyn Kriley

While you wait for Theo of Golden

Peruse compelling novels that explore the importance of community and connection.

January 27, 2026 · Kaitlyn Kriley

While you wait for Theo of Golden

Peruse compelling novels that explore the importance of community and connection.

January 27, 2026 · Brea Black

Artsy Crafty Library: More crafting, less scrolling

Many crafters find working with their hands is a good way to lower stress & improve well-being. Whether you're looking to learn new craft skills or to further your knowledge, the library has resources to help.

January 27, 2026 · Brea Black

Artsy Crafty Library: More crafting, less scrolling

Many crafters find working with their hands is a good way to lower stress & improve well-being. Whether you're looking to learn new craft skills or to further your knowledge, the library has resources to help.

January 26, 2026 · Stephen Ferrell

3 Classic rock albums move from lost to found

Thanks to some spiffy new re-releases you can discover long-lost classic rock treasures.

January 26, 2026 · Stephen Ferrell

3 Classic rock albums move from lost to found

Thanks to some spiffy new re-releases you can discover long-lost classic rock treasures.

January 23, 2026 · Luanne Webb

Great Read Alouds: Cozy winter reads

Check out our recommendations of picture books that can kick-start the love of reading.

January 23, 2026 · Luanne Webb

Great Read Alouds: Cozy winter reads

Check out our recommendations of picture books that can kick-start the love of reading.

January 23, 2026 · Julie Nelson

The Reel World: No place to call home

Watch documentaries that take you across the country to visit communities struggling with affordable housing.

January 23, 2026 · Julie Nelson

The Reel World: No place to call home

Watch documentaries that take you across the country to visit communities struggling with affordable housing.

January 22, 2026 · Katie Keckeisen

Discover an easier way to access local history materials

The library is home to a robust collection of items relating to Topeka and Shawnee County history including archives, photographs, ephemera and three-dimensional objects.

January 22, 2026 · Katie Keckeisen

Discover an easier way to access local history materials

The library is home to a robust collection of items relating to Topeka and Shawnee County history including archives, photographs, ephemera and three-dimensional objects.

January 15, 2026 · Arion Beals

Kid Tested, Librarian Recommended: Kids classics

Classic stories are a little like a favorite blanket. They make you feel warm and cozy, and make you want to come back to them again and again.

January 15, 2026 · Arion Beals

Kid Tested, Librarian Recommended: Kids classics

Classic stories are a little like a favorite blanket. They make you feel warm and cozy, and make you want to come back to them again and again.

January 13, 2026 · Andrew Ross

What YA' Reading: Sci-Fi Romance

Read every Romantasy there is? Check out captivating Sci-Fi stories with plot-central romances next.

January 13, 2026 · Andrew Ross

What YA' Reading: Sci-Fi Romance

Read every Romantasy there is? Check out captivating Sci-Fi stories with plot-central romances next.

January 12, 2026 · Julie Nelson

Lost in the Stacks: Sisters in Death

Discover an intriguing link between the infamous Black Dahlia case and a gruesome murder in Kansas City.

January 12, 2026 · Julie Nelson

Lost in the Stacks: Sisters in Death

Discover an intriguing link between the infamous Black Dahlia case and a gruesome murder in Kansas City.