Dr. Samuel Crumbine: Topeka’s public health pioneer

Dr. Samuel Crumbine: Topeka’s Public Health Pioneer

During the first two decades of the 20th century, Kansas became a leader in public health education thanks to Dr. Samuel J. Crumbine, the secretary for the Kansas Board of Health. Several of the programs and campaigns he developed would go on to be adopted in other states. Crumbine’s efforts were aimed at making Kansans healthier and preventing the spread of deadly diseases such as typhoid and tuberculosis.

Frontier Doctor

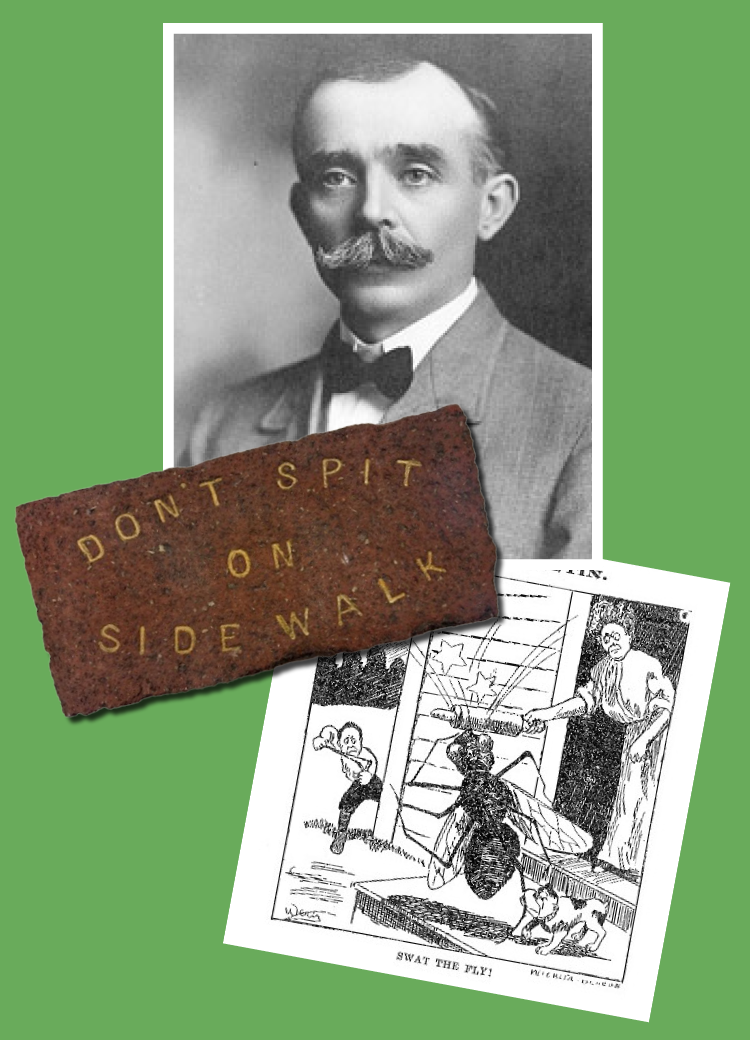

Dr. Samuel J. Crumbine,

ca. 1909.(TSCPL)

Samuel J. Crumbine was born in Emlenton, Pennsylvania, on September 17, 1862. He received a medical degree from the Cincinnati College of Medicine and Surgery. While he was still in school, Crumbine purchased a half-interest in a drugstore in Spearville, Kansas, and worked there during school vacations to pay off the debt.

After graduation, Crumbine permanently moved to Kansas, and opened a practice in Dodge City. He not only treated families in the area but was also often called upon to treat the victims of Dodge City’s gunslingers. Crumbine’s work in the rough and tumble cattle town made him a well-respected physician across the state. His life in Dodge City would later serve as inspiration for the character of Doc Adams on the TV show Gunsmoke (played by fellow Kansan Milburn Stone).

Dr. Crumbine also operated a pharmacy in Dodge City.

(Dodge City Times, Sept. 5, 1889)

Public Health Crusader

In 1899 Crumbine was named to the Kansas Board of Health. The organization was created in 1885 to oversee the health of the people of Kansas. But the Board had relatively little power and a small annual budget to accomplish their mission.

In 1904 Crumbine was named Secretary of the Board of Health. With the power of this new position, he began implementing several public health programs and lobbying the State for more money. Interest in public health had been growing nationwide due to several public food safety scandals, as well as the publication of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. Crumbine used these as a springboard to launch a series of public health education programs aimed at combating the spread of diseases such as tuberculosis and typhoid. The success of these programs in Kansas led to them being used by many other states throughout America.

Crumbine also realized if the Board was going to be successful with any of its initiatives, the public had to understand what the scientist were saying. He would later write “officials must translate scientific knowledge and public health facts into terms the average person can understand, then explain in terms equally simple how to apply this knowledge to every-day living.” One of the ways this was accomplished was through the Board of Health’s monthly publication the Bulletin.

“Swat the Fly!”

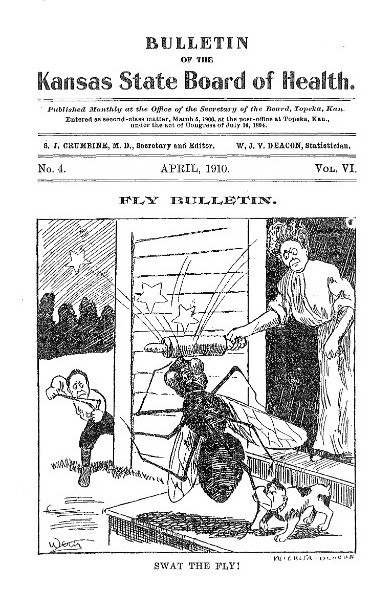

The cover of the April 1910 issue of the Bulletin

of the Kansas State Board of Health. (TSCPL)

One of Crumbine’s most famous public health campaigns was against the common house fly. Many doctors and scientists knew flies were disease carriers, but most people simply considered flies a nuisance. To fight this Crumbine and the Board of Health began a massive public relations campaign with the catchy slogan: “Swat the Fly!” Posters with information on the dangers flies posed were printed and placed in post offices and railroad stations. The entire April 1910 issue of the Bulletin was dedicated to discussing flies, the diseases they could carry and how to deal with them.

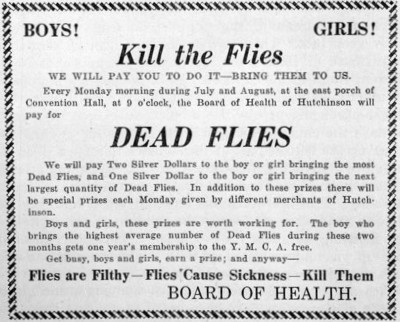

This ad for a fly bounty program sponsored

by the Board of Health of Hutchinson

(Image courtesy of kansasmemory.org,

Kansas State Historical Society, Copy

and Reuse Restrictions Apply)

Crumbine publicly encouraged the use of a “fly-killer” or “fly bat” to rid homes of these pests. To tie this into his program he began calling it a flyswatter and the name stuck. Crumbine also asked local sanitary officers to start fly swatting incentive programs. These “fly bounties” offered citizens (usually children) money in exchange for quarts of dead flies. In Topeka in 1914 the price for a quart of dead flies was 15 cents (about $5 today).

“Ban the Public Drinking Cup!”

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, one of the most feared and easily spread diseases was tuberculosis. Crumbine sought to stop everyday habits he believed were helping to spread tuberculosis through two large health campaigns.

One was to ban the use of public, or “common,” drinking cups. Before water fountains and disposable cups, the water coolers in school houses, on train cars and at offices had a single metal cup that was used by everyone. Crumbine realized the danger these shared cups posed while on a train trip back to Dodge City. He saw a man he knew to be suffering from tuberculosis drink from the public cup in the train car. The next to use the cup was a mother and her young child. Crumbine knew he had to stop the use of these cups if the spread of tuberculosis was to be curtailed.

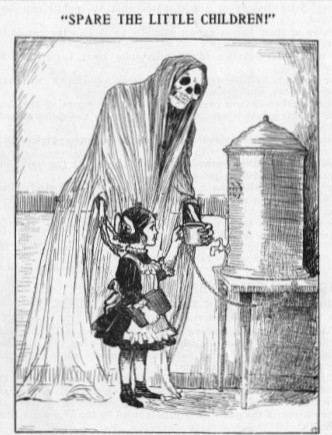

One of the many cartoons that was used

in the campaign to ban the public

drinking cup. (TSCPL)

Crumbine and the Board of Health began another media blitz. This one featured haunting cartoons and posters that featured skulls and the skeletal figure of death around the water coolers with a shared cup. These were plastered in every public building and printed in newspapers throughout the state, leading the Kansas State Legislature to ban the use of public drinking cups in 1909. It was the first state in the nation to do so.

“Don’t Spit on the Sidewalk!”

The second of Crumbine’s public health campaigns against the spread of tuberculosis was aimed at the common practice of people spitting on the floor or the sidewalk. Since tuberculosis spread when people coughed, sneezed or spoke, Crumbine believed spitting also spread the disease.

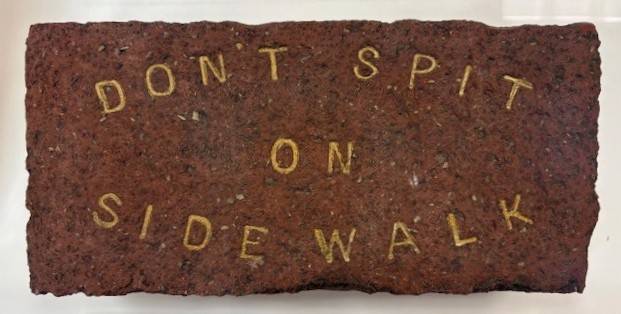

One of the bricks made to dissuade people from spitting in public and potentially spreading diseases. (TSCPL)

To combat the prevalence of public spitting, Crumbine contacted brick makers throughout the state to create sidewalk bricks with the words “Don’t Spit on the Sidewalk” stamped into them. As Crumbine later wrote in his autobiography, Frontier Doctor, “many prefer the word expectoration to spit. But the shorter word drove the idea home.”

The bricks were soon part of sidewalks in cities throughout Kansas. While many of the original bricks have since been removed to make way for more modern sidewalks, several have found their way into museums and private collections. There is even one at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History.

“The health of one depends on the health of all”

After serving almost two decades as secretary, Crumbine resigned from the Kansas Board of Health in 1923. The politics in Kansas had changed and many saw Crumbine’s method as somewhat autocratic. He moved to New York City where he served as executive director of the American Child Health Association until he retired in 1936. He died in Long Island, New York, in 1954.

Crumbine’s legacy lives on in the public health programs he spearheaded in Kansas. The programs “Swat the Fly” and “Ban the Public Drinking Cup” were adopted by almost every other state and county health department in the nation. Crumbine is also remembered through two awards that bear his name: the Samuel J. Crumbine Consumer Protection Award, which is awarded annually by the Conference for Food Protection, and the Samuel J. Crumbine Medal, the highest award given by the Kansas Public Health Association.

This Samuel J. Crumbine Medal for Meritorious Service in Public Health was awarded in 1996 to Robert Harder. (TSCPL)

In 2017 the Kansas Health Institute - in collaboration with Downtown Topeka, Inc., and the Downtown Topeka Foundation – dedicated a pocket park in front of the Health Institute’s building on Kansas Avenue. The park features a bronze sculpture of Dr. Crumbine, as well as bike racks shaped like flyswatters.

To learn more about Dr. Samuel J. Crumbine’s life and work, you can visit the Topeka Room to view our latest display on this public health pioneer.