Local cookbooks are a window to the past

One of the hidden gems of the library's Topeka Room is the collection of local cookbooks. Most of them are the kind created as fundraisers for churches and clubs. The organization collected recipes from members, and then sent them to a publisher to print and bind them. Members sold to their friends, family and community. Profits went to the club or group. We cookbooks from all sorts of Topeka-based churches, clubs and businesses – there are even a couple compiled by library staff.

One of the hidden gems of the library's Topeka Room is the collection of local cookbooks. Most of them are the kind created as fundraisers for churches and clubs. The organization collected recipes from members, and then sent them to a publisher to print and bind them. Members sold to their friends, family and community. Profits went to the club or group. We cookbooks from all sorts of Topeka-based churches, clubs and businesses – there are even a couple compiled by library staff.

Looking through these cookbooks, you can see that tastes have changed over the years. Other aspects of history also creep in. Technology like refrigeration and stoves, what was cheap to eat and what was fancy, even things like the standard size of a can have changed over the past 100 years.

Early 1900s

I picked out a few cookbooks from different time periods and started by looking at the oldest one – The Fireless Cooker: How to Make It, How to Use It, What to Cook by Caroline B. Lovewell and Frances D. Whittemore, published in Topeka in 1908. At that time, kitchen stoves would have used coal or wood, which meant they needed to be much larger to have a compartment for coal as well as an oven. Refrigerators were literally ice boxes, an insulated cabinet with space for a block of ice in the bottom and food in the top. Built in cabinets and counters weren’t even a thing, you had to put in your own shelves for storage.

I picked out a few cookbooks from different time periods and started by looking at the oldest one – The Fireless Cooker: How to Make It, How to Use It, What to Cook by Caroline B. Lovewell and Frances D. Whittemore, published in Topeka in 1908. At that time, kitchen stoves would have used coal or wood, which meant they needed to be much larger to have a compartment for coal as well as an oven. Refrigerators were literally ice boxes, an insulated cabinet with space for a block of ice in the bottom and food in the top. Built in cabinets and counters weren’t even a thing, you had to put in your own shelves for storage.

It would have been a whole lot more work to clean up coal ash daily and constantly empty a drip tray from your icebox. The solution the authors of The Fireless Cooker propose is right there in the title. They talk about “a kettle or other vessel that can be heated, enclosed in a box or other outer shape, with enough insulating material between them to prevent the heat in the kettle from escaping.”

Saving time & effort

The main point is to heat the food, then insulate it very well so it continues to cook for several hours. The book goes on to describe some methods of insulating an existing box or cabinet or building one from scratch. It's the 1908 version of a crock pot, I said to myself. Not exactly, but both are tools for saving labor. We don't have to haul coal today, but we still want to save time and effort. Long, slow cooking is one way to do it.

The recipes in this book don't have lists of ingredients like we'd expect to see. They're written in narrative form with entire paragraphs of instructions. The recipes are also written to be made in a fireless cooker, so I moved on to look at recipes in a book with more conventional cooking methods in mind.

1930s

The next book I looked at was published in 1930. By that time gas stoves were more common. Some people had refrigerators, but they were very expensive. The average income in the U.S. in 1930 was $1,368 per year. A refrigerator cost upwards of $150 – more than a month's salary. The average income in the U.S. now is around $53,000 so you'd be looking at a $6000 fridge!

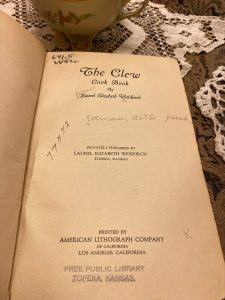

The Cookbook of Laurel Elizabeth Weiskirch: CLEW to 1500 American and Foreign Recipes is the book I explored. I spent a little time trying to find out something about Weiskirch’s life, but couldn’t find much. Using the library's subscription to Newspapers.com I searched her name in Topeka papers from the early 20th century. I found a few mentions of her and her husband, Armin A. Weiskirch, in the society pages. They seem to have been a well-off couple who lived in the Potwin neighborhood.

The Cookbook of Laurel Elizabeth Weiskirch: CLEW to 1500 American and Foreign Recipes is the book I explored. I spent a little time trying to find out something about Weiskirch’s life, but couldn’t find much. Using the library's subscription to Newspapers.com I searched her name in Topeka papers from the early 20th century. I found a few mentions of her and her husband, Armin A. Weiskirch, in the society pages. They seem to have been a well-off couple who lived in the Potwin neighborhood.Weiskirch's book has some narrative recipes like the earlier book, but many list the ingredients first as in most modern cookbooks. Some of the recipes would still work and sound good today. I would totally roast a pork loin with onions and apples as she instructs on page 76. I didn't know cake pops existed in 1930, but under Holiday dessert is a recipe for mixing fruit cake crumbs with grape juice and molding it around chocolate covered cherries. They're not on a stick, but it's the same concept. The Thanksgiving staple of marshmallows on sweet potatoes is here too.

Uncommon ingredients

However, many recipes have ingredients that aren’t common in 2022 or just sound downright unappealing. I'm sure chopped celery leaves in meatloaf taste fine, but I've never made anything that specifically calls for the leaves. I'll definitely skip macaroni stewed in kidney sauce.

Looking at the salad chapter, nearly all the salads call for mayonnaise dressing, even the fruit salads. This is where I went off on a tangent. I am a huge fan of learning the history of words, and not a big fan of mayo. I found salad used to refer to cold meat with mayo more like tuna salad than a green salad. Read this article to learn the origin of the word salad. Mayo on fruit still sounds bad to me, but it makes a little more sense why they call it a salad.

Late 1960s

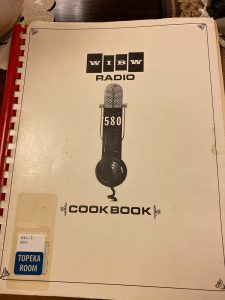

Next, I chose The WIBW Cookbook, which includes recipes sent in from Topeka and all over the WIBW 580AM listening area, and was published in 1968. What cooking advances have there been over those 38 years since 1930? I notice most of the recipes are still from scratch, but some of them use margarine instead of butter. A few recipes are low calorie and use saccharin or other artificial sweeteners, which is also new.

Next, I chose The WIBW Cookbook, which includes recipes sent in from Topeka and all over the WIBW 580AM listening area, and was published in 1968. What cooking advances have there been over those 38 years since 1930? I notice most of the recipes are still from scratch, but some of them use margarine instead of butter. A few recipes are low calorie and use saccharin or other artificial sweeteners, which is also new.

Nervously, I turned to the salad section to see what developments had occurred. I found a recipe for mayonnaise on the first page of the section! Yes, most of the salads contain mayo, sour cream, cream cheese, marshmallows or that staple of American cooking - gelatin.

Gelatin

Let's address the wibbly-wobbly elephant in the room: what was up with all the gelatin?! Who decided covering food in gelatin and molding it into a ring was the best cooking method ever? I took a detour to find out.

Gelatin was used as far back as ancient Egypt, but for most of its history it wasn't easy to make. It's made by the unpleasant process of boiling animal bones. You boil and strain it multiple times to get a product that is clear and flavorless. Because of this lengthy process, serving fancy molded gelatin dishes was a way to show off that you were rich enough to have servants doing the work for you. Picture French lords and ladies of the 1700s dining on molded gelatin, smug about not having had to boil bones themselves.

Fast forward to 1895, Jell-O fruit flavored gelatin is invented in the United States. It takes a few years to catch on and once it does, it does not stop for several decades. First, people were just excited about how easy it was to make powdered gelatin, it's a novelty. Then refrigerators became common, making it faster and easier to chill the molds and keep them cool. (It will start to go soft above 80 degrees – not feasible in Kansas summer without a fridge!) By the middle of the 20th century serving a gelatin mold with perfect layers of food arranged within was a peak housewife skill.

Fast forward to 1895, Jell-O fruit flavored gelatin is invented in the United States. It takes a few years to catch on and once it does, it does not stop for several decades. First, people were just excited about how easy it was to make powdered gelatin, it's a novelty. Then refrigerators became common, making it faster and easier to chill the molds and keep them cool. (It will start to go soft above 80 degrees – not feasible in Kansas summer without a fridge!) By the middle of the 20th century serving a gelatin mold with perfect layers of food arranged within was a peak housewife skill.

By the time the WIBW cookbook was published in 1968, gelatin recipes had been passed down through generations, and they still come out at holidays. Regardless of whether it contains fruit, meat or veggies, calling it a “salad” apparently stuck too.

Late 1980s

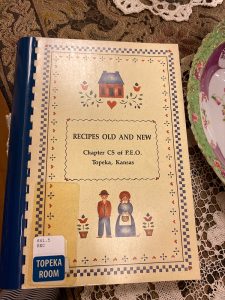

Finally, I looked at one cookbook published during my life span. Recipes Old and New by Chapter CS of P.E.O. (Philanthropic Educational Organization, a women's charitable organization) was published in 1989. It doesn't say which recipes are old and which are new, but here is the kind of food that's very familiar from my Midwestern childhood. Some recipes use packaged foods like a box of Jiffy cornbread mix, frozen peas or a can of cream of mushroom soup. (In our house we ate a lot of Hamburger Helper, another semi-homemade dish.) There are lots of casseroles, still a lot of mayonnaise and perhaps we have hit the peak of gelatin delights. Is mustard out of a jar too boring for you? Try the recipe below!

Finally, I looked at one cookbook published during my life span. Recipes Old and New by Chapter CS of P.E.O. (Philanthropic Educational Organization, a women's charitable organization) was published in 1989. It doesn't say which recipes are old and which are new, but here is the kind of food that's very familiar from my Midwestern childhood. Some recipes use packaged foods like a box of Jiffy cornbread mix, frozen peas or a can of cream of mushroom soup. (In our house we ate a lot of Hamburger Helper, another semi-homemade dish.) There are lots of casseroles, still a lot of mayonnaise and perhaps we have hit the peak of gelatin delights. Is mustard out of a jar too boring for you? Try the recipe below!

Mustard Mousse

1 packet unflavored gelatin

¼ cup lemon juice

4 eggs

¾ cup sugar

3 Tbsp. Dijon mustard

½ tsp. Salt

½ cup cider vinegar

½ cup water

½ pint whipping cream, whipped

2 Tbsp. Chopped parsley

Sprinkle gelatin over lemon juice; let stand 5 minutes to soften. In saucepan, mix eggs, sugar, mustard, salt, vinegar, and water; beat well. Add gelatin mixture. Stir constantly over moderate heat until mixture begins to thicken. Do not boil. Refrigerate until almost set. Oil a 4 cup mold. Fold whipped cream and parsley into gelatin mixture. Pour into mold and cover with plastic wrap. Refrigerate several hours or overnight. Serves 8.

This might taste decent with a slice of ham, but it’s an awful lot of work for mustard flavor. Gelatin salads aside, these cookbooks are still a solid source for made-from-scratch dinners, desserts, and more, plus a peek into the kitchens of Topeka's past. Stop by the Topeka Room and take a look!