Uncovering the history of local festivals

Content

There are lots of festivals and fairs in September and October all over Kansas. Historically, fall festivals were associated with the harvest season. In just about every culture around the world, from ancient times to the present day, there is some kind of autumn harvest festival. When people grew most of their own food, this was the time of year they would know if they had enough to stay well fed through the winter. People celebrated a (hopefully) bountiful harvest and gave thanks to whatever god or gods they believed in.

Topeka's first fall festival

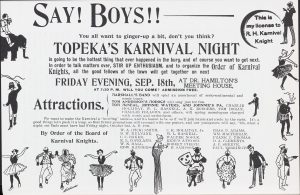

Here's an ad calling for a meeting of “boys” interested in planning the Karnival, as they were calling it.

In modern times, we're not as directly dependent on the local harvest, but the tradition of harvest festivals continues. In Topeka city leaders organized the first fall festival in 1895 and held the event in 1896. I used my favorite source the Bulletin of the Shawnee County Historical Society to find out some details. Don't you want to ginger-up a bit after reading that? It doesn't say where “Dr. Hamilton's meeting house” is, so I guess you just have to know already. But the article Topeka's Fall Festivals by Joseph G. Gambone published in 1975, tells us what the Karnival was like.

A week of activities

"The first Fall Festival and G.A.R. Reunion held during the last week of September, 1896, were glorious affairs," wrote Gambone. "One observer described the celebration as a full week of 'wonderful pageantry, floats, fireworks, carnival pranks, sham battles, band contests, firemen's tournaments, camp fires, and civic, military and floral parades —a time of unmixed pleasure, innocent fun and revelry, and something for every day and every night of the week.' The festivities began with a great parade on September 28 which was viewed by over 50,000 visitors, including some 10,000 Civil War veterans who had journeyed to Topeka for the reunion, and was followed with a series of exciting week-long activities.” (I had to look up G.A.R. It stands for Grand Army of the Republic. It was an organization for veterans who fought for the Union in the Civil War.) Gambone's article also talks about some of the political activity surrounding the festival even though it wasn't supposed to be political. I'll leave it to you to read more on that if you're interested.

Festival queen brings drama

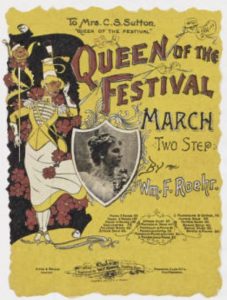

The first festival was a resounding success and in 1897, they raised even more money. 1897 was also the 25th anniversary of the founding of the Santa Fe Railroad, so organizers combined the two celebrations to make the second year bigger and better. That year's parade had 6,000 men, 12 marching bands, 55 floats and stretched for four miles! The festival queen was Mrs. C.S. Sutton, who played a big role in the organization of the festivals. She wore $25,000 worth of diamonds rented from Tiffany & Co., a luxury jewelry company based in New York. That was a lot of bling at the time and is nearly a million dollars in today's money.Unfortunately, the queen's bling became the downfall of the carnival. Despite intensive fundraising, the festival committee had three dollars left after they paid most of their bills. And they hadn't paid for Mrs. Sutton's costumes or carriage rental yet. Festival organizers sued Mrs. Sutton personally over the bills, but the court ruled she wasn't responsible to pay them. The festival committee eventually raised more funds to pay the costs. But by 1898 Topekans were complaining about all the money spent for no tangible benefit. I'm guessing they also stopped donating, because the 1898 festival was only a one day event instead of a week-long celebration, and the third year (which I'll get to shortly) was the last of the original fall festivals in Topeka.

The first festival was a resounding success and in 1897, they raised even more money. 1897 was also the 25th anniversary of the founding of the Santa Fe Railroad, so organizers combined the two celebrations to make the second year bigger and better. That year's parade had 6,000 men, 12 marching bands, 55 floats and stretched for four miles! The festival queen was Mrs. C.S. Sutton, who played a big role in the organization of the festivals. She wore $25,000 worth of diamonds rented from Tiffany & Co., a luxury jewelry company based in New York. That was a lot of bling at the time and is nearly a million dollars in today's money.Unfortunately, the queen's bling became the downfall of the carnival. Despite intensive fundraising, the festival committee had three dollars left after they paid most of their bills. And they hadn't paid for Mrs. Sutton's costumes or carriage rental yet. Festival organizers sued Mrs. Sutton personally over the bills, but the court ruled she wasn't responsible to pay them. The festival committee eventually raised more funds to pay the costs. But by 1898 Topekans were complaining about all the money spent for no tangible benefit. I'm guessing they also stopped donating, because the 1898 festival was only a one day event instead of a week-long celebration, and the third year (which I'll get to shortly) was the last of the original fall festivals in Topeka.

Who was C.S. Sutton?

I'm going to back up here, because I'm still wondering about Mrs. C.S. Sutton. Can we maybe find out her first name? I typed the name “Sutton” into the Bulletins database and found out lots of tidbits about Mr. Sutton and a few mentions of Mrs. Sutton's activities. But I couldn't find her first name anywhere, how frustrating. Other than Mrs. Sutton, Gambone really doesn't tell us much about women's contributions to the festival.

I'm going to back up here, because I'm still wondering about Mrs. C.S. Sutton. Can we maybe find out her first name? I typed the name “Sutton” into the Bulletins database and found out lots of tidbits about Mr. Sutton and a few mentions of Mrs. Sutton's activities. But I couldn't find her first name anywhere, how frustrating. Other than Mrs. Sutton, Gambone really doesn't tell us much about women's contributions to the festival.

Women's role in festival planning

Luckily for us, Euphemia Page tells us more about festival planning activities in her 1953 article Topeka's Fall festivals were exciting. Page tells us the women were in charge of Flower Day, one of the five days of celebration in 1896. She doesn't say which women exactly, but calls them all “Mrs.” so we can guess that they were all married, possibly to the men who were also planning the festival. They did a variety of fundraising activities and planned the Flower Day float.  Page's article has a delightful word-for-word transcript of the women's conversation of how Kansas and Topeka should be represented on the float. While reading it, I tried to picture the women and imagine the conversation. Who was amiable and open to compromise? Who was annoyed they didn't get their way? What else they might have been thinking about at the time? Page goes on to tell us about how Mrs. Sutton got stuck with the bills but adds more detail about the dress and jewels. One dress was “Silver brocade with design of lilac blossoms in white and gold, full skirt and train two and a half yards long, a point waist, puffed sleeves, and high jeweled collar.” I was curious about what this might have looked like, and found this article about fashions from this decade.

Page's article has a delightful word-for-word transcript of the women's conversation of how Kansas and Topeka should be represented on the float. While reading it, I tried to picture the women and imagine the conversation. Who was amiable and open to compromise? Who was annoyed they didn't get their way? What else they might have been thinking about at the time? Page goes on to tell us about how Mrs. Sutton got stuck with the bills but adds more detail about the dress and jewels. One dress was “Silver brocade with design of lilac blossoms in white and gold, full skirt and train two and a half yards long, a point waist, puffed sleeves, and high jeweled collar.” I was curious about what this might have looked like, and found this article about fashions from this decade.

The mysterious first queen

When I started writing this article, I didn't intend to focus on the festival queens. But since Mrs. Sutton was such a big part of the story of why the festival ended, I thought it was only fair to look into the other two. Weirdly, there's not much about the first queen. Page mentions a “Queen of Red Fire” as part of one of the week's themes, and Gambone writes that the queen was “'Lorena, Queen of the Carnival' and whose identity was kept secret from all as she appeared only one night dressed in her mask and carnival costume.” Those were the only mentions from these two articles. I didn't take the time to find out more about her, because I got interested in the third queen.

The third queen was imported

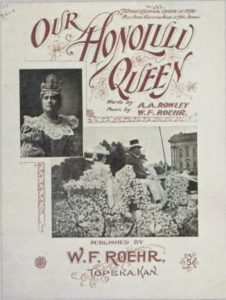

Last name is misspelled in the newspaper's caption - it should be Loke.

The third queen has quite a story behind how she came to preside over the fall carnival in Topeka. Ana Kanaina Loke, or “Anna Rose” as she was introduced in Kansas, traveled from Hawaii to preside over the parade. Why would the parade committee bring someone all that way? I remembered that Hawaii was one of the last states to join the United States, which didn't happen until sometime in the mid-1900s... that was as close as I could recall. So I looked it up and Hawaii became a state in 1959.

It wasn't a bad idea to want to get to know the people and culture of the new territory, although I question how much you can do that by meeting one individual. The community leaders in Hawaii who were asked to choose a queen would have known the person they sent would likely be the only Pacific Islander the folks on the mainland had ever seen.

Instant celebrity

Ana Kanaina Loke was the daughter of a German-born American father and a mother who was a native Hawaiian of Polynesian descent. She was a schoolteacher in Hilo, Hawaii. Loke traveled by boat to San Francisco. As soon as she arrived she was an instant celebrity. It must have been like winning a reality show and becoming famous overnight, only without the competition. According to The Kansas Weekly Capital of Friday, September 30, 1898 (available through the library's subscription to Newspapers.com) she was greeted by thousands of people during her train journey to Topeka. This article also describes her heritage, her manners, her physical stature and even her skin tone, painting a detailed portrait for those who couldn't witness the festivities in person. In the days leading up to the festival parade, Topeka society held multiple receptions in private homes and in the state Senate chamber. At these events Loke would shake hands and converse with anyone and everyone. According to newspapers in Kansas and Hawaii she was a massive hit. What we don't know is how did Loke feel about all this? Was she in favor of Hawaii becoming a United States territory? How did she feel about her parents' two different cultures? Did the sudden burst into celebrity bother her or was she cool as a cucumber about it?

Ana Kanaina Loke was the daughter of a German-born American father and a mother who was a native Hawaiian of Polynesian descent. She was a schoolteacher in Hilo, Hawaii. Loke traveled by boat to San Francisco. As soon as she arrived she was an instant celebrity. It must have been like winning a reality show and becoming famous overnight, only without the competition. According to The Kansas Weekly Capital of Friday, September 30, 1898 (available through the library's subscription to Newspapers.com) she was greeted by thousands of people during her train journey to Topeka. This article also describes her heritage, her manners, her physical stature and even her skin tone, painting a detailed portrait for those who couldn't witness the festivities in person. In the days leading up to the festival parade, Topeka society held multiple receptions in private homes and in the state Senate chamber. At these events Loke would shake hands and converse with anyone and everyone. According to newspapers in Kansas and Hawaii she was a massive hit. What we don't know is how did Loke feel about all this? Was she in favor of Hawaii becoming a United States territory? How did she feel about her parents' two different cultures? Did the sudden burst into celebrity bother her or was she cool as a cucumber about it?

Representing a culture

Even though she was treated like an actual queen by the festival officials, she was also being examined and inspected as a representative of a culture that had been foreign until quite recently. It might have been a lot of pressure, but she also might have been the type of person who genuinely enjoyed socializing on a very large scale. Perhaps we could find out by more reading and research. But right now, all I can say is that by the time Loke left, the festival committee was in debt and the festivals were done. Although there wasn't an 1899 festival, of course that was not the end of all the fall festivals in Shawnee County. The Warde-Meade Apple Festival and the Cider Days Market have both been going for about 40 years. Perhaps that's a topic for next autumn. I wonder if there are festival queens.