Local History: Willie Lyman, the boy who survived a great fall

Willie Lyman: The Boy Who Lived

In October 1955 retired Topeka dentist Dr. William Lyman sat down with Topeka Daily Capital reporter Peggy Greene for an interview. The interview had nothing to do with dentistry. Greene was there to ask Dr. Lyman about something that happened 65 years before. When he was 16 years old, William Lyman fell from the dome of the Capitol and lived.

An Unforgiving Job

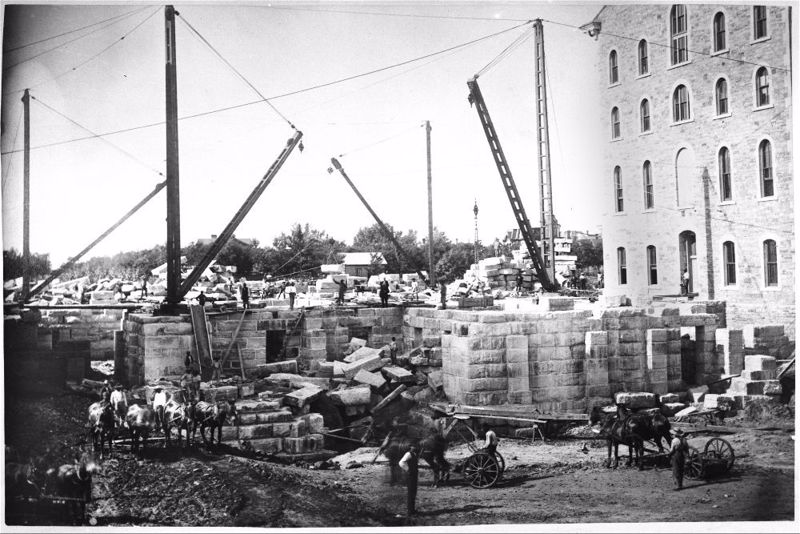

The construction site at the Kansas State Capitol, circa 1886. (Image courtesy of kansasmemory.org, Kansas State Historical Society, Copy and Reuse Restrictions Apply)

The construction site at the Kansas State Capitol, circa 1886. (Image courtesy of kansasmemory.org, Kansas State Historical Society, Copy and Reuse Restrictions Apply)

The state capitol is a point of pride for most Kansans. The classical design, executed in limestone and topped by the distinctive copper dome, make it a prominent feature in the city’s skyline. Construction of the Capitol began in 1866 and wasn’t officially completed until 1903.

The job of a construction worker at the site was a hard one, often in dangerous conditions. A good portion of the building project was completed using manual labor and simple machines like pulleys and hoists. Without modern-day safety measures, there were accidents, injuries and sadly, deaths.

At least seven individuals died during the almost 40 years of construction and six of those were due to falls. The earliest recorded fall-related casualty occurred Aug 16, 1886. A 58-year-old stone mason named Young Campbell lost his balance while attempting to maneuver a wheelbarrow carrying a large stone around a corner on the exterior scaffolding and fell 40 feet. He died from his injuries a few hours later.

During the next three-and-a-half years two more workers died from falls. William Cullins lost his life on Nov 20, 1888, after a misstep while working on the third story of the north wing of the statehouse. On Sept 21, 1889, Charles Howell fell 120 feet from where he was working on the roof of the south wing.

“A Boy’s Awful Fall”

The Topeka Free Library was once housed on the Capitol grounds. This image was taken in 1889 and the dome can be seen under construction to the left. (TSCPL)

The Topeka Free Library was once housed on the Capitol grounds. This image was taken in 1889 and the dome can be seen under construction to the left. (TSCPL)

When work on the dome officially began in 1889 safety conditions had not improved that much. Simple wooden scaffolding and ordinary ladders were used to aid workers who were constructing the stone “drum” that would eventually support the copper dome.

Three boys scampered up these wooden ladders on the afternoon of April 6, 1890. It was Easter Sunday and the teenagers – William Curtis, Willie Lyman and an unnamed friend – had slipped past the watchman on site. They hoped to climb up as high as they could and get a view of the city.

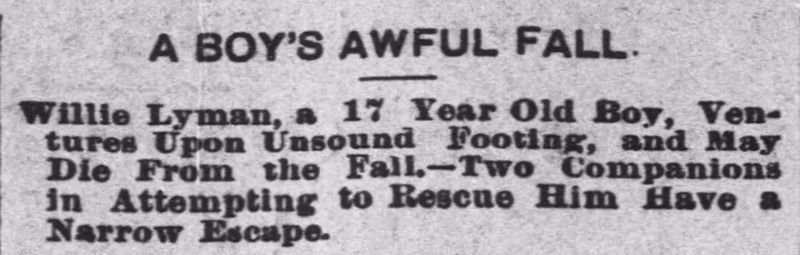

The boys had managed to climb up to the first floor of the dome, which was made up of iron girders and terracotta tiles. Newspaper accounts from the time differ on what exactly happened next. The Topeka State Journal said, “young Lyman ventured out upon what seemed a safe extension from the floor.” While the Topeka Daily Capital stated the boys “recklessly began jumping over the tiling.” No matter the reason, Lyman stepped off the solid platform and on to the terracotta tiling around the dome. Unable to bear weight, the tiles crumbled and Lyman fell.

Instinctively Lyman reached out and grabbed on to an iron floor beam. He clung to it for dear life as he dangled over 80 feet of empty space. His two friends rushed to help him, but as they grasped on to him, the terracotta under them began to give way as well. The boys had to make the terrible decision to let go of Lyman or risk falling through themselves.

Lyman held out by his fingertips as long as he could but at some point his fingers slipped. As his terrified friends looked on Lyman disappeared into the dark abyss. When recalling the incident to Greene years later Dr. Lyman said he remembered thinking as he fell, “My goodness, will I never get to the bottom?”

Recovery Uncertain

Willie Lyman's fall was covered by all the major newspapers in Topeka. (Topeka State Journal, April 8, 1890)

Willie Lyman's fall was covered by all the major newspapers in Topeka. (Topeka State Journal, April 8, 1890)

His two friends, meanwhile, had heard him land but nothing more. They scrambled back down the ladders and scaffolding, screaming for help. The commotion roused the State House janitors, some local police officers and a group of citizens. The newly formed rescue party hurried into the basement of the building to try to find Lyman. The basement was “as dark as night,” a newspaper reported. It took the group a while to find the poor boy, who was lying unconscious on a pile of brick and debris. Almost everyone believed he was dead.

The police called for Dr. J.P. Lewis whose office was on Kansas Avenue. Under his guidance the group carefully loaded the still-unconscious Lyman into a wagon and took him home. Dr. Lewis then examined Lyman’s body and found that, miraculously, he had no broken bones. His internal injuries, however, were extensive.

When he regained consciousness the next morning, Lyman was able to recount certain details of his fall. But he kept coughing up blood and complaining of intense pains in his head and torso. Dr. Lewis determined Lyman had suffered an internal rupture between his heart and his lungs. The Topeka newspapers reported, “it is uncertain whether he will live or die.”

A Long-Lived Survivor

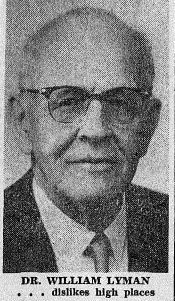

Photo: Dr. William Lyman in 1955 with a caption that goes without saying. (Topeka Daily Capitol, October 9, 1955)

Photo: Dr. William Lyman in 1955 with a caption that goes without saying. (Topeka Daily Capitol, October 9, 1955)

Of course, Lyman did survive his injuries. He spent almost a month recovering, remembering later that spent most of that time laying “in a kind of numbness” and immobile while the wounds healed.

About a month later, Lyman was up and about. He was healed enough to give a recitation as part of the Western Avenue Mission Sunday School. Lyman also went back to the capitol to see how far he had fallen. It is believed he fell at least 80 feet from the first level of the dome into the basement.

After Lyman’s fall construction on the building continued. Sadly, four more workers lost their lives before it was completed. One worker – Jack Williams – fell to his death just more than a month after Lyman suffered his fall. The building was considered complete in 1903, but portions remained under construction until 1917.

Lyman grew up, married Ollie May Markley in 1898, and went to dental school in Kansas City. After passing his exams, he returned to Topeka and opened a practice with his brother, Dr. Samuel Lyman, that operated for 43 years. Willie Lyman died in Glendale, California, in 1961 at the age of 87. Amazingly, he suffered no lasting effects from his fall, except for a life-long fear of heights.