Local History: Topeka body snatching scandal

The Topeka Body Snatching Scandal

The entrance gates to Rochester Cemetery, where two of the three bodies were stolen (Photo courtesy of Rochester Cemetery)

The entrance gates to Rochester Cemetery, where two of the three bodies were stolen (Photo courtesy of Rochester Cemetery)On the morning of December 9, 1895, Clarence Scott, the sexton of Rochester Cemetery, was making his rounds when he noticed a grave he had filled only the day before appeared to have been disturbed. Fearing the worst, Scott decided to dig down into the grave to investigate. He had only gone a few inches when his shovel struck the wooden top of a coffin. With his suspicions confirmed, Scott ran off to alert the authorities. Over the next several days, more details came to light of a ghoulish scandal involving several of the most prominent men in Topeka, as well as the state’s first medical school.

The Kansas Medical College

The first home of the Kansas Medical College was located at 521 W. 12th Street (TSCPL)

The first home of the Kansas Medical College was located at 521 W. 12th Street (TSCPL)The Kansas Medical College had been formed in 1889 in Topeka and was the first established medical school in Kansas. It was also the only school in the state that awarded the degree of Doctor of Medicine. Its founders were made up of many of the leading physicians in the state.

At the time of the scandal, medical colleges throughout the United States were facing a lack specimens on which to practice their skills. This was due to the fact no one donated their bodies to science during the 18th and 19th centuries. Most of Western civilization believed if your body was dissected, you would be unable to rise whole on the day of resurrection. As science communicator Mary Roach put it, “dissection was thought of, literally, as a punishment worse than death.”

And yet, people wanted their physicians to have full knowledge of the human body and its inner workings. Such knowledge was only obtainable through laboratory dissections during medical training. Most states including Kansas only allowed for the bodies of convicted criminals who died in prison or in a hospital to be claimed by medical colleges to use in dissection. And even then, the law had so “many exceptions and contingencies” that almost no legal specimens were made available to the Kansas Medical College. It was an unspoken rule that students at the medical college had to provide their own cadavers for dissection, either by doing the dirty work themselves or hiring someone else to do it.

The First Victim

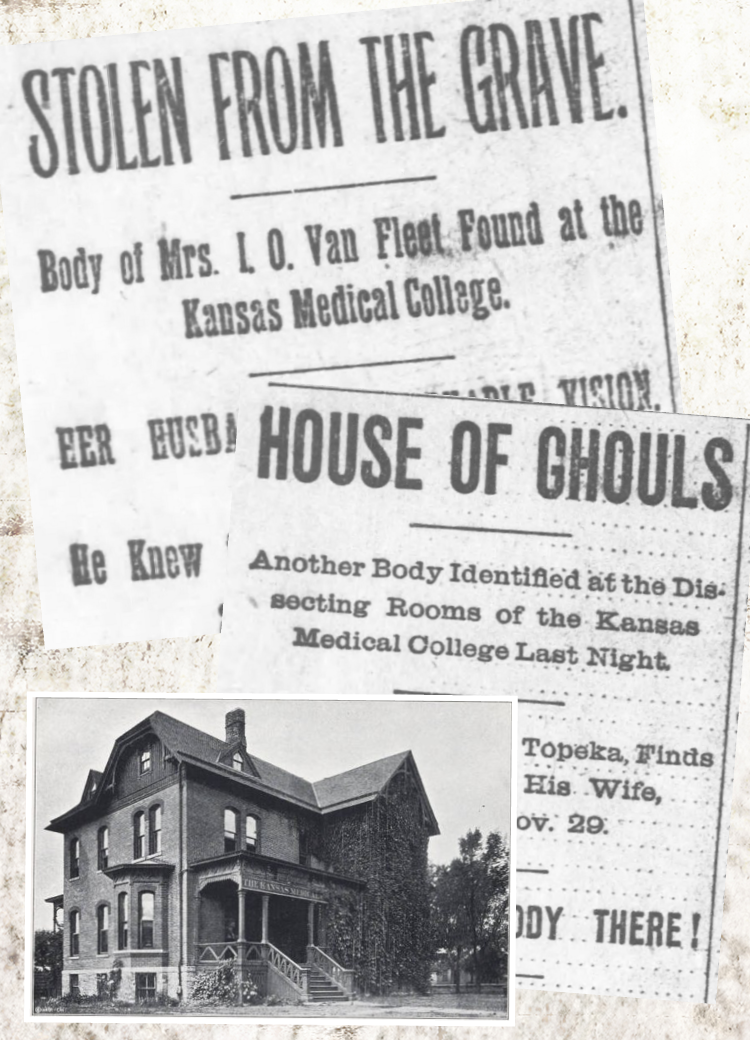

The first of many headlines that detailed the grave of Amelia VanFleet being desecrated (Topeka Daily Capital, Dec. 10, 1895)

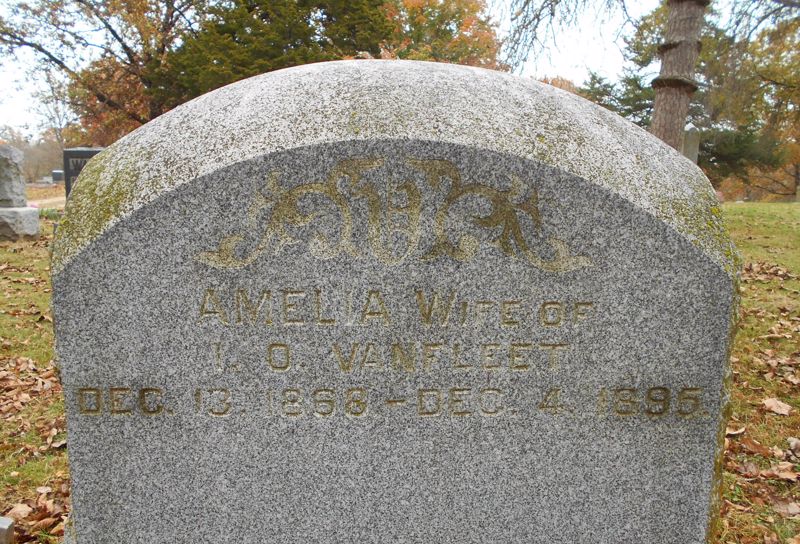

The first of many headlines that detailed the grave of Amelia VanFleet being desecrated (Topeka Daily Capital, Dec. 10, 1895)Only the day before Sexton Scott’s gruesome discovery, the body of 27-year-old Amelia VanFleet had been interred at Rochester Cemetery. Amelia died on December 4, 1895, due to complications from tuberculosis. She was laid to rest next to two of her children who had also recently died from diphtheria.

Upon finding that her grave had been tampered with, Sexton Scott went to the VanFleet home to give Amelia’s husband, Isaac, the terrible news. Isaac and his brother both accompanied the sexton back to the cemetery. They dug up the rest of the grave and discovered that Amelia’s coffin was empty except for the clothes she had been buried in.

Suspicions immediately fell on the Kansas Medical College, located at the corner of 12th and Tyler, where students dissected the bodies of criminals as part of their studies. The police obtained a search warrant for the college and took along Amelia’s brother-in-law in case a body needed to be identified.

At the college the men were taken by Dr. J.E. Minney, the dean of the college, to the dissecting room. Two bodies were on the exam tables, but neither were Amelia. As Dr. Minney tried to escort them from the room, the police opened a closet and inside was the body of Amelia VanFleet. Although most of her identifying traits had been removed, her brother-in-law was able to identify the body by a mole on her shoulder and a slightly deformed foot.

All the doctors and students claimed they had no idea how that body had come to be at the Medical College. However, the police immediately arrested the school’s janitor, a student named Samuel Johnson, on suspicion he had been the one who received the body. His $500 bond was paid by Dr. Minney and he was released.

Two More Bodies

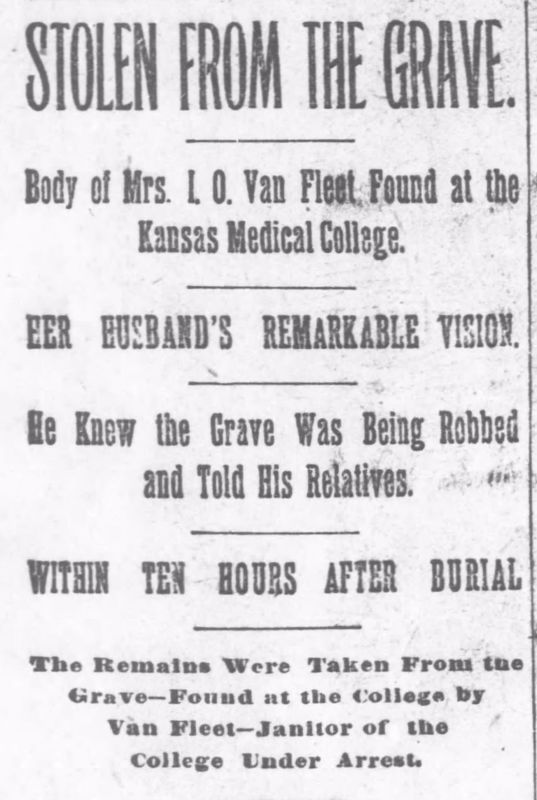

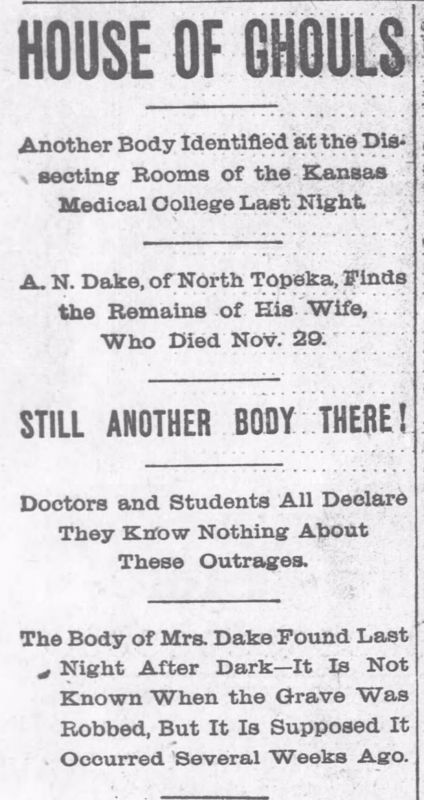

The Topeka papers spared the public no details on the gruesome discoveries at the medical college (Topeka Daily Capital, Dec. 11, 1895)

The Topeka papers spared the public no details on the gruesome discoveries at the medical college (Topeka Daily Capital, Dec. 11, 1895)The next day, it was revealed that another body at the school had been stolen from its grave. She was identified as Matilda Harris Dake who died of consumption on November 29 and was buried at Rochester only a week before Amelia VanFleet. When her grave was unearthed, her coffin was also found empty save for the burial clothing. When the authorities went back to the medical college they discovered the other two bodies had been tampered with in an attempt to make them more difficult to positively identify.

The third body was identified on December 11 as Hannah Lillis, the wife of a local blacksmith. She had died of tuberculosis and had been buried at the Catholic Cemetery. She was identified by the undertaker who prepared her body for burial.

Once again Samuel Johnson was arrested and his bond paid for by Dr. Minney. The college faculty released a statement condemning the actions of whoever had brought these bodies into the college and pledged “to use all proper efforts to ascertain the persons who may have desecrated graves and to do what they can to assist the proper authorities in bringing any guilty persons to justice."

Public Outcry

The night of December 11 found Topeka simmering with outrage. The Topeka Daily Press reported that crowds of “angry, sullen and determined” men were congregating in the streets and there was talk of burning down the college or blowing it up with dynamite. The papers also reported hearing “many threats” made against Dr. Minney.

Dr. J.E. Minney was the dean of the Kansas Medical College and received many threats during the most heated moments of the grave robbing scandal (Pasadena Star News, Jul 8, 1927)

Dr. J.E. Minney was the dean of the Kansas Medical College and received many threats during the most heated moments of the grave robbing scandal (Pasadena Star News, Jul 8, 1927)The city physician Dr. M.R. Mitchell also got caught up in the scandal when George Reedy accused Mitchell of offering to hire him and a friend named Carr to rob a grave at Rochester and deliver the body in Reedy’s wagon to the medical college. Reedy was quick to say he and Carr hadn’t actually done the deed. When they had arrived at the meeting place Dr. Mitchell said they were too late and he’d given the job to another man.

Soon every medical man and student in Topeka was suspected of having knowledge of the grave robberies. Dr. Mitchell had to be extracted from an angry group of men who were yelling “Hang Mitchell!” With talk that a mob was forming in North Topeka that would soon attack the medical college, Governor Edmund Morrill called out the military and law officers to guard the medical college and patrol the streets. Thankfully, the threat of mob violence never materialized.

Justice served?

On December 18 former city scavenger Marcus E. Lowe was arrested for grave robberies. Lowe was already well-known to law enforcement in Topeka who had arrested him several times for violent acts. Only a few months before Lowe had “committed a murderous assault on a man at the fairgrounds.

In January 1896 a grand jury was formed to investigate the grave robberies and in February released their verdict. Dr. J.E. Minney and school janitor Samuel A. Johnson were indicted on three counts of knowingly receiving a stolen body. Two other students, A.W. Vaniman and Louis C. Duncan, were indicted on one count of knowingly receiving a stolen body. And Marcus E. Lowe was indicted on three counts of grave robbery. A formal trial was held in 1897, which found only Samuel Johnson and Marcus Lowe guilty. Both were fined $500 and Lowe was given a 30-day jail sentence. Johnson’s conviction was later overturned on appeal and Lowe was pardoned by Governor John Leedy.

Even though he was alleged to have a role in grave robbing scandal, Samuel Johnson went on to be a medical doctor and member of the Kansas Medical College faculty (TSCPL)

Even though he was alleged to have a role in grave robbing scandal, Samuel Johnson went on to be a medical doctor and member of the Kansas Medical College faculty (TSCPL)Despite the public indignation the charges did not leave a lasting tarnish on the reputations of those involved in the crimes. Samuel Johnson graduated from the Kansas Medical College only a few weeks after the trial and was awarded a new set of surgical instruments for having the highest grades in his class. Dr. Johnson later joined the faculty of the medical college. Dr. Minney continued to serve as the dean of the Kansas Medical College until 1904, and practiced medicine in Topeka until he and his family moved to California in 1909. And the medical college itself continued educating Kansas doctors for several more years. It became part of Washburn College in 1903 and then became part of the University of Kansas in 1913.

But for those who had the graves of their loved ones desecrated, the emotional effects were lasting. Isaac VanFleet, Patrick Lillis and Albert Dake, the husbands of the grave robbing victims, each brought a damage suit against the Kansas Medical College, but it appears nothing ever came of these. Isaac VanFleet had his wife’s body reburied in Rochester Cemetery, but both Lillis and Dake refused to say where they reburied their wives. Their trust in the sanctity of burial grounds had been destroyed.

Amelia VanFleet's gravestone at Rochester Cemetery (findagrave.com)

Amelia VanFleet's gravestone at Rochester Cemetery (findagrave.com)Explore more local history

You can discover more local history stories in the library's Topeka Room. Explore our books, pamphlets, clippings and other written sources that tell the story of Topeka’s unique history. You will also find photographs, prints, posters, scrapbooks and audio-visual materials that help bring this history to life. The Topeka Room houses the library’s local history collection. Our digital collection includes the Sanborn maps and the Sherwood Smith blueprints.